Epona's Well

Epona’s Well

Epona’s Well, artist Karen Kramer, curator Hanna Laura Kaljo, Jupiter Woods, 2015.

““Climate change has been dealt with in the arts on a representational, symbolic and thematic level, without substantially changing what an artistic practice (or rather the whole arts-industrial complex) could be when faced with such intricate distributed phenomena” ”

This research-led curatorial project was developed in the context of a master’s thesis in Curating at Goldsmiths College, 2015. It started as a study of how the Anthropocene was conceptualised within the humanities, along with theories arising from Ecological Epistemology at large. I felt drawn to address some of the key shifts in perception that these narratives were inviting me, as a cultural practitioner, into. The process entailed taking a critical look at the traditional exhibition as a product-oriented format, going on to dismantle the research/artwork dichotomy to offer an alternate pathway to making public. Challenging what is commonly raised to the foreground and what is considered as background, the intention of the project was to let emphasis fall on the intricate processes of association across diverse materials, revealing their simultaneous presence within a research practice.

I proposed that even as the Anthropocene circles human-centred polemics, it simultaneously opens into a wider perspective “at Earth magnitude” (Morton, 2014), shifting the focus from individual acts to systems of intra-action (Barad, 2012:6). These alterations in perception and scale begin to position human actions in a broader network of consequences. The “environment”, formerly a background to human activity, becomes the foregrounded event. Applying this to the practice of contemporary curating—fundamentally a compositional, organising and often discriminating practice—a potentially meaningful presentational gesture could instead entail recognition of a web of converging source materials, while enabling these to exist side-by-side without applied uniformity. I worked closely with the New York-born, London-based artist Karen Kramer to create a 10-day presentation that embodied a point on the trajectory of her artistic research process: the often forsaken moment before the coming together of elements into a unified work of art, in this case a film.

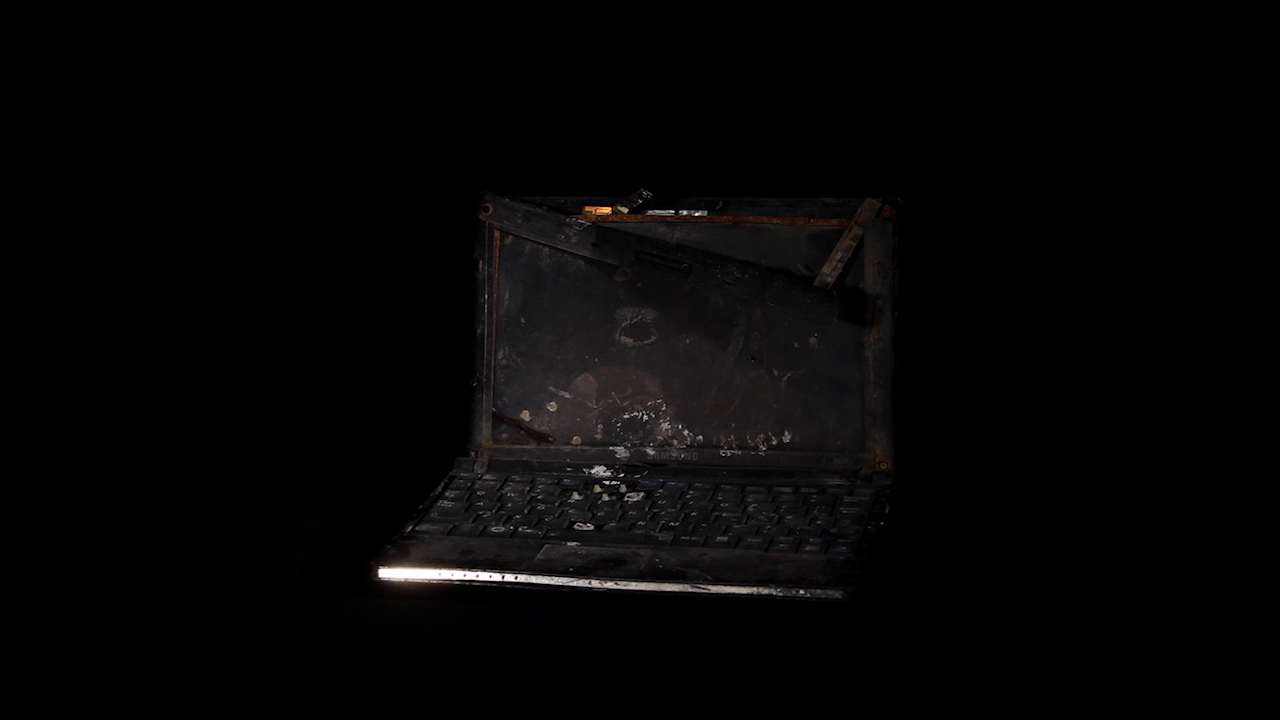

The central feature of Epona’s Well was a body of found fragments, artefacts and organic remains, spanning centuries and diverse species, some already, others soon extinct. Fractured gadgets from the early days of technological acceleration were juxtaposed with fossils, a hex and other elements. The display comprised of dark blue walls and softly spot-lit objects referenced the common museological exhibition, yet intentionally departed from a preoccupation with the surviving. Instead, it focused on the non- or barely surviving: the "flows of substances that wash across time” (Pennell, 2010:30) yet do not find representation in leading historical museums. Arranged in a constellational manner in a darkened room, the presentation of these objects followed free association, yet was inevitably ordered according to a film makers shape-sensitive intuition. The remnants were lit with occasional spotlights, while many of the objects faded into shadows and ambiguity. The darkened scenery might have resembled a film set, while the hardly perceivable arrangements of objects in the dimmest areas of the walls intended to evoke lack of information and an initial distance from what was being looked at.

“The display comprised of dark blue walls and softly spot-lit objects referenced the common museological exhibition, yet intentionally departed from a preoccupation with the surviving. Instead, it focused on the non- or barely surviving: the “flows of substances that wash across time” (Pennell, 2010:30) yet do not find representation in leading historical museums.”

Gathered by the artist from the shores of the River Thames, the objects and their presentation furthered Kramer’s ongoing exploration of trauma on varying scales, from the human to the geological. The project thus elaborated on the act of collecting as an act of mourning, the symbolism of burial and the construction of the archival. The objects were further studied through the mechanism of video: a projection onto a black wall in the gallery presented a number of the fragments, either alone, in pairs or groups of three. Rotating fluidly around their own axis, they appeared to be floating in a non-space, violently withdrawn from their ‘original’ time and situated meaning. A sequence of layered, fragmental sounds of male and female singing alongside the video, marked a sorrowful disruption in the otherwise silent display.

A thread of narrative entwined with and occasionally overlaying the display of objects was that of Epona: a goddess in the Gallo-Roma tradition, a protector of horses and a symbol of fertility. The periodically emerging fragments of sound were extracts from various iterations of the song Stewball, composed in memoriam of an 18th century racehorse. Epona’s Well was, thus, both depository and reliquary, memorial and inventory: offerings from the river to the horse. Kramer approached these narratives as stratification, wherein certain layers are pushed to the surface while others recede, expanded as a curatorial methodology of the presentation as a whole.

In contrast to the darkened ambiance of the gallery, a reading room facing the garden accommodated natural daylight. The ammonite-coloured walls—a paint specifically chosen considering its reference to the fossil of an extinct marine cephalopod mollusc featured in Kramer’s collection of found fragments—supported shelves made of white painted metal and chipboard. These held 36 reference points. Two public reading group events looked more closely at three materials extracted from the reading room, and served as occasions to go deeper into some of the themes circulating within Kramer’s practice, in conversation with the artist herself. The first event focused on the contrary movement of burial and archaeological excavation; the museological concept of material durability; and the inherent deviance of objects. The second considered the concept of deep time at the dawn of the Anthropocene; of empathy with the sea and river; and traced sedimentations of the mind.

The project was a prelude to Kramer’s FVU commission, a 22 minute film The Eye That Articulates Belongs on Land. Shot in Shiretoko National Park in the far north of Japan, and within watchful radius of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor, the film offsets beguiling images of unspoilt nature with graphic visual evidence of the ‘re-wilding’ of the landscape around the atomic plant since particular areas became off-limits to human access. Unseduced by romantic notions of wild nature as a wellspring of recovery or transformation, Kramer’s film is a reminder of how our perceptions of the natural environment are often deeply subjective, and prone to being clouded by myth, or partial knowledge.

The Eye That Articulates Belongs on Land, 2016, Karen Kramer.