Let the field of your attention.... soften and spread out

Let the field of your attention….soften and spread out

a research project and exhibition

This project is a response to the urgency of recovering a slower pace of engagement. How do we begin composing a cultural sector that is attentive to the vital phase of dormancy – the potent silence between notes – within a creative process, alongside valuing productivity? With extractivism, exhaustion and imbalance as both individual and ecological realities, this question holds value.

‘Let the field of your attention….soften and spread out’ was conceived in the framework of a commissioned curatorial proposal for the 5th Tallinn Photomonth, an international biennial of contemporary art across mediums, and finalised as the inaugural exhibition of Kai Art Center on Tallinn Bay, Estonia, between 20 September - 1 December 2019.

The submission of the preliminary proposal catalysed a year-long research and development process, which culminated in a ten-week-long exhibition and public programme. At Kai, an audience was invited into a spatial and temporal composition featuring works by eight artists, the majority of whom are either from or in dialogue with the Nordic-Baltic region: Marie Kølbæk Iversen (DK), Sandra Kosorotova (EST), Pia Lindman (FIN), Andrea Magnani (IT), Elin Már Øyen Vister (NOR), Carlos Monleon Gendall (ES), Sam Smith (AUS) and Nele Suisalu (EST). Their practices span sculpture, film and video, textile design, sound, dance, socially-engaged and therapeutic facilitation.

The project has since been discussed in lectures held at the Estonian Academy of Arts and Frame Contemporary Art Finland. In 2021, it was the focus of an Exhibition Studies MA thesis by a researcher at the Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki, analysing dramaturgy as a curatorial tool.

What follows is a brief reflection from a curator’s viewpoint on how this project came to be, leading to an overview of its realisation at Kai. This page is comprised of five sections: Research, Concept Development, Curatorial Approach, Composition and Appendix (video documentation, press and credits). I invite you to share in some of the, otherwise hidden, movements that guided this compositional practice.

1

Research

The point of departure of the proposal was the urgency of recovering a slower pace of engagement. In the context of a biennial concerned with societal changes in a fast-paced world increasingly mediated by cameras, screens and images, I first considered the impact of this culture of appearances and perpetual manufacture on inner life and mental wellbeing. I then asked: how do we begin composing a cultural sector that is attentive not only to productivity but also to the vital phase of dormancy – the potent silence between notes – within a creative process? With imbalance and exhaustion as both individual and ecological realities in the west and further afield, this question held value.

“Due to the fast pace of urban life, there is no longer any room for silence and dimness. This in turn has removed ‘completeness’ from our lives, as the forces of darkness play a pivotal role in releasing feeble and tired ‘being’, thus allowing for something new to emerge.”

As an author, I came to write this proposal from the intersection of two frames of reference. On the one hand, I had grown up along the coast where Kai Art Center is situated, thus my aesthetic sensibility, the way I perceive and make meaning of space and silence, has been shaped by the vast natural landscapes and seasonal peculiarities of this coastline and the wider Nordic-Baltic area. On the other hand, I had been living and working in London, UK, for close to a decade at the point of writing. Spacious emptiness and silence take on a different meaning in this densely populated, globally connected megacity. Here, these qualities need to be generated from within. I set myself a curatorial challenge to compose an exhibition from the ground up, by way of attunement to this particular place and region in Estonia, at the same time working with the topic as it applies to a global community in an age of extractivism, climate change and metal health crisis.

“A lot of our pain, depression, sense of isolation comes from a loss of contact with the natural forces. Our nervous systems and hormonal systems are on overload, creating further chaos, stress and lack of resilience. Sustainability is a somatic theme as much as an ecological principle.”

In my practice as a research-led curator, I have incorporated embodiment as a method of inquiry alongside theory and discourse. The project at hand, concerned with notions of pace, rhythm and balance, also called for a take on somatic study: the inquiry into one’s lived body by observing and exploring oneself through sensing and moving. In thinking about how to create the conditions for the dormant phase of a creative process to be valued, I came to the conclusion that this would entail slowing down enough to be able to perceive subtle movements. In instances like this, the research process comes to resemble that of an anthropologist or a choreographer. As my objective was to work from the ground up and communicate a felt sense of the Nordic-Baltic region within the walls of the gallery, I set out to derive the language of the exhibition from a lived experience of the area. The scope of this territory was then mapped by movement.

In addition, I gathered data about how these lands have imprinted themselves on others who live with and through them. In a journal entry from the winter of 2018, I note:

At 7:30am the sun appears on the horizon. Over the course of the next two hours, as dreams linger at the edge of awareness, the sky slowly brightens with a tint of red. I’ve been heading our onto the frozen lake before noon to soak up daylight, pale blushing face turned skyward. “The Sun is a God”, a local woman I met on the ice told me. I’ve started to comprehend why she would liken the sun to divinity. One easily slips into despair as the day sinks shortly after noon. At the house, we keep a candle near, but sometimes fail to tell each other apart from the darkness that envelops us. Indeed the capacity to generate warmth has acquired a kind of sacredness. Lit by the radiant Milky Way we gather around bonfires and steaming food for comfort and companionship. Yet in the depth of the night, when sleep is scarce, each faces the dark alone in their own little body. We greet the sun with a simple gesture of aliveness. “How to make one’s way through a time of darkness?”, I asked her. “By tending the tiny fire within you with kindness. By holding a torch up for others”, she responded.

In practice, the research process unfolded alongside a year-long R&D project I was engaged in at the time with the support of Arts Council England. This involved spending intentional time in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Estonia to learn about the impact of environmental conditions, particularly the long, dark winters and extreme weather, on artistic sensibility and societal wellbeing. This line of inquiry led me from the Nacadia Therapy Forest Garden near Copenhagen, a research- and therapy-based garden providing mental health rehabilitation, to Europe’s deepest iron mine in Kiruna above the Arctic Circle, whose inhabitants are fleeing due to the ground collapsing beneath their homes and feet. Rather than aiming for a comprehensive study, which was not feasible at that time, the breadth of the research was that of an artistic inquiry.

“Western culture favours brightness and visible productions, whilst it does not value, or even fears, the dark, or the hidden. The secret germination of plants and even that of a human being are not assessed as it would be worthy of them. (…) Scorning this secret process of the living risks mistaking appearance(s) for the appearing of life, a risk that lies in our tradition from the very beginning and that has transformed the west into a culture of uprooting.”

2

Concept Development

From the aforementioned experiences emerged the concept for what the exhibition would ideally feel like. The key principles I was working with were:

The feeling that there is a whole (the exhibition) that cannot be accessed directly, all at once, rather it can only be experienced over time. Something always remains hidden.

That the exhibition ‘comes forth’ at sunset and the frequency of actions rise as we approach the winter solstice, the darkest time of the year. What is in the dark is in fact dynamic.

That the exhibition moves through different degrees of visibility and publicness, from intimate private moments to events that invite a large group to gather. Each event, each work, invites a particular form and pace of engagement. We value quality over quantity.

That the choreography of bodies mimics that of the Baltic Sea meters from the gallery: audiences gather and disperse in a sort of ebb and flood. The interior is attuned to the exterior.

The choice of artists, their contributions in dialogue with the architecture of Kai, brought this perception into form. In researching and inviting artists to partake, I was making decisions based on their sensibility, their working process and their own line of inquiry.

3

Curatorial Approach

“She has now begun to dye fabrics by hand, using medicinal plants. One of these – fireweed – grows in abundance in between the area where she grew up and where she is currently living. This vibrant plant is the first to emerge after a forest fire. It restores and rejuvenates the forest floor, preparing the ground for new beginnings. Fireweed flower essence, in turn, is a rehabilitating balm, which helps the energetic network of the emotional body to recover from burnout. ”

The final selection of eight artists featured individuals with whom I had already cultivated a working relationship as well as those with whom we met in view of this exhibition. Our meetings took place in dance studios in Oslo, Tallinn and rural northern Italy, underground tunnels in Copenhagen, the Arctic Art Summit in Rovaniemi and the forests of subarctic Sweden, amongst other places.

As much as I rely, in the moment of laying the foundation of a given project, on my curiosity and perception of what is not yet represented within my own culture, the crux of my role as a curator is to support, encourage and amplify voices other than my own. Thus the curatorial approach I employ is first and foremost person-centred, meaning I prioritise the creative process and developmental trajectory of the individual artist over a specific object of art. This involves listening to which next step they are keen to bring into fruition and considering how the exhibition as a whole can support them in doing so. An approach of this kind is particularly fruitful in the production of new work, as was the case on five occasions in the context of this project. When we are working with existing pieces, like three of the artists involved, the conversation is around devising the most meaningful pathway for their work to become public.

Kai Art Center before renovation, Tallinn, 2019.

Kai Art Center after renovation, Tallinn, 2019.

4

Composition

Kai Art Center, 20 September - 1 December 2019

The title of the exhibition ‘Let the field of your attention….soften and spread out’ is derived from a bodywork exercise (‘Landing…. time to be still’ by Miranda Tufnell) inviting one’s attention to settle within. Over the course of ten weeks, a programme of actions and gatherings activate the architectural space of Kai and the installed works within its fabric.

The timeline of the exhibition, curving down toward the winter solstice.

Kai Art Center, a former submarine factory, sits directly on the harbour and comprises an open plan gallery, two smaller rooms at the rear of the space and an auditorium. Standing in the main gallery for ‘Let the field…’, one would be met with an exhibition design receptive to shifts in daylight. Technical director Tõnu Narro and I approached this architectural space less as a self-contained white cube and more as an interior permeated by the ever-changing weather of the coastline upon which the building rises. As a visitor one is invited to bring attention onto the nature of light and the passing of time. The exhibition opens in proximity to the autumn equinox and moves toward the winter solstice, the darkest time of the year with only a few hours of daylight.

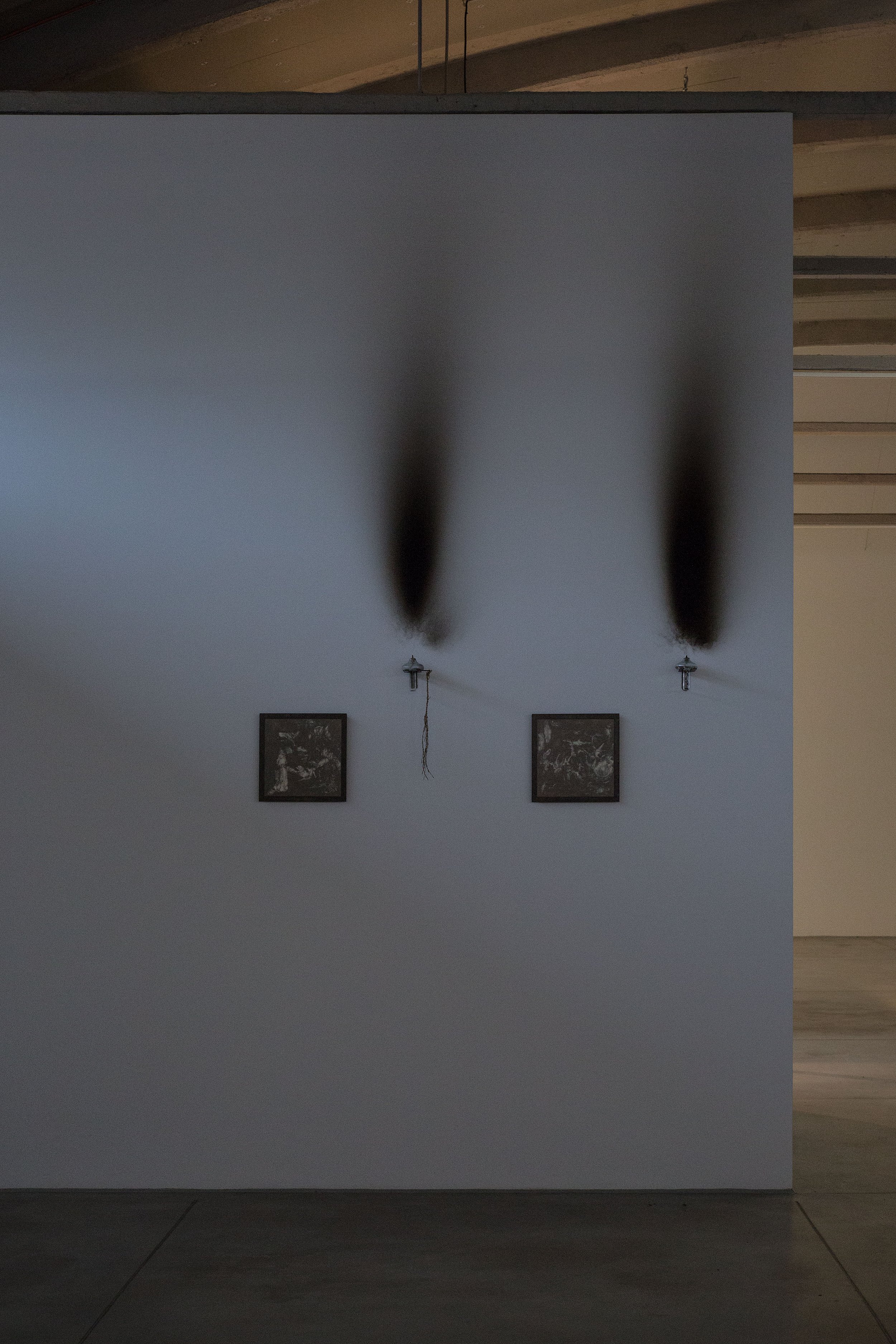

Before sunset, the only source of light within the gallery is the work of Marie Kølbæk Iversen titled ‘Io/I’ (2005-ongoing): four large-scale, 3D animated satellite images of Jupiter’s innermost moon Io projected into the room. Playing on the different connotations of Io (a celestial body, a female figure within Roman mythology, an Italian word for ‘me’) this work evokes the perpetual process of disintegration out of which new configurations of landscape and selfhood emerge. At sunset, a daily ritual of lighting four oil lamps as part of the work of Andrea Magnani adds a tint of warmth to the room. These intricately layered, candle-lit charcoal drawings shimmer, inviting various interpretations of what the images depict. The third and final installation in the main gallery is by Carlos Monleon Gendall titled ‘Fasting of the Luna moth’, a series of small-scale sculptures placed on the concrete floor with soft plinth-like blocks. These hand-made pieces either rest within shade or emerge illuminated by the light emanating from the two other works mentioned above. On two evenings, Monleon Gendall leads on a gathering of tea-drinking, movement and gentle touch.

In the auditorium, Sam Smith’s 50 minute film ‘Lithic Choreographies’ (2018) set in the Swedish island of Gotland is screened at night-fall. Filmed over the course of two years, this work attends to the island’s 200-thousand-year geologic history and the circulation of minerals in economic, cultural and agricultural contexts shaping Gotland today. The title of the work refers to the formation of the island during the Silurian period and its slow movement from the equator to its current location in the Baltic Sea.

In one of the smaller rooms at the rear of the gallery is an installation by Sandra Kosorotova titled ‘IMMUNITY’. Placed in a circle on the floor and hung from railing are pieces of clothing and folded textile: medical gauze, non-violent silk, wool and cotton dyed with local healing plants like fireweed, stinging nettle, black chokeberry and onion. Her practice is concerned with the theme of exhaustion as it is provoked by living under the conditions of neoliberalism as a vulnerable body. Over the course of three weekends, she leads workshops of textile making, reading, writing and listening with a group of women from the area she grew up in, sharing strategies for moving through the darker months of the year with care.

In the space opposite, a room has been prepared to deliver a traditional Finnish healing technique called Kalevala Bone Setting. Two years after a severe mercury poisoning, Pia Lindman dreamt that she could see people’s bones through their skin and soon came upon this old healing modality, which she now practices. “Our bones have developed over hundreds of thousands of years and open us to a memory beyond cultural forms”, she says. Making treatments, which she does for two people during the exhibition, is both an explorative and creative event for her. In the process of reading the language of a particular body or a particular place, Lindman directs her perceptions into Diagrams. A couple of these are hanging on the walls of the room. Two sets of headphones hold soundscapes recorded during her travels to Kuusamo in northern Finland, including one from the bottom of the artificial lake Sompio. In late November, a small group gathers around stories from her journey.

At sunset, which over the course of the exhibition shifts from 7.05pm in September to 3.41pm in November, dancer and performance artist Nele Suisalu steps into the centre of the main gallery to alter the quality of the space through the use of movement and the voice. ‘Allow yourself (…)’ is an improvised session in front of a live audience, delivered on five occasions highlighting the gradual shortening of the day. For this piece, Suisalu is drawing on principles from the 5 Rhythms moving meditation practice and Fasciapulsology, the latter being a manual therapy facilitating the release of tensions in the connective tissue layer. Both entail turning inward to perceive the physiological and emotional experiences of the body in order to initiate movement from these perceptions. The audience is invited into meditative awareness of their own inner state as they witness the dance.

One afternoon in early November, Elin Már Øyen Vister, an artist, composer and forager from the Arctic island of Skomvær, leads a group on a mindful walk from the steps of Kai toward a nearby park, a former medieval cemetery. ‘A proposal for an ephemeral memorial. A sonic walk and deep listening to Kalamaja’ is organised in collaboration with curatorial assistant Kaisa Maasik and local guests Ene Lukka, Evelin Reimand and Kadi Uibo. Those walking are invited to listen to stories, told in spoken word and music, about the stratified history of this ground, as well as to heed those buried here as is the custom on All Soul’s Day. This process is informed by Pauline Oliveros’ philosophy of Deep Listening, meaning, the art of paying attention.

5

Appendix

“I think the main strength of this exhibition is the clarity with which it implements a phenomenological curatorial approach.”

“Hanna Laura Kaljo highlight the responsibility that humans take upon themselves in service to preserving their home planet. In these circumstances she perceives an opportunity for ethical deepening. Instead of speaking about the anthropocene in a political and scientific language, she explores how one can work with it as a visual symbol that stands for the existential crossroads ahead. This is a kind of feminist counter-acopalypse introducing an extensive, grassroots adaptation programme.”

“Essentially, it feels as if the exhibition is about the passing of time, measured against your own experience, or vice versa. Making this palpable, however, is a difficult task. When walking through the exhibition space, many of the works have a distinct air of being suspended, of something missing. I do not mind this in the least; the opportunity to come back to a new experience next time is exciting; but I also know some parts of it will remain out of reach for me. Just like visitors, artists also come and go, making sporadic appearances throughout, leaving the audience to witness what they leave behind, and to wonder about the potentialities yet to be called into being. This very dynamic equation is nevertheless held together by a strong concept, and, in a more material presence, by the curator. I love seeing that kind of care put into in exhibitions. It is not performative care, neither on the part of the curator nor on the part of the artist. For that, I am grateful.”

“The exhibition is representative of a type of curator seldom seen in Estonia, an aesthete by birth—someone who possesses attributes that one cannot learn. Someone who appreciates fine execution, minimalism and is highly sensitive to nuances. ”

Credits

Curator: Hanna Laura Kaljo. Assistant: Kaisa Maasik. Artists: Marie Kølbæk Iversen, Sandra Kosorotova, Pia Lindman, Andrea Magnani, Elin Már Øyen Vister, Carlos Monleon Gendall, Sam Smith and Nele Suisalu. Exhibition Design: Tõnu Narro. Exhibition Team: Anastassia Dratšova, Sille Kima, Karin Laansoo, Kadri Laas, Kulla Laas, Eeva Lillemägi, Kadi-Ell Tähiste, Laura Toots, Natalie Mets. Photography: Aron Urb, Hedi Jaansoo and Johan Pajupuu. Video: Stella Saarts. Supported by: Akusmata, British Council, Cultural Endowment of Estonia, Enterprise Estonia, European Regional Development Fund, Embassy of Spain in Estonia, Estonian Ministry of Culture, Royal Norwegian Embassy, Office for Contemporary Art Norway, Nordic Culture Point, Estonian Folk Culture Centre, The Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland, Finnish Institute in Estonia, Danish Arts Foundation, Tallinn Culture Department, TelepART, Viru Keskus. The research phase of the exhibition benefitted in part by the Developing Your Creative Practice grant by Arts Council England.